Dune was like the anti- Star Wars , undoing everything Lucas’s trilogy did to make sci-fi a friendly place. A New Hope took audiences to far away galaxies, sure, but it smoothed the transition into the fantastical with a simple, recognizable tale: A gentle farmhand meets a wise old man and a cowboy, gets himself a sword (of sorts), and goes adventuring. It’s almost baffling, in retrospect, that producer Dino de Laurentiis, who bought the rights to the notoriously obtuse Dune project in 1978, one year after Star Wars became a hit, could look at Herbert’s novel and think that something as warm, friendly, and accessible could be squeezed from its pages.

Herbert’s book offered a meticulously detailed saga of a dark future where royal houses war for control of the desert planet Arrakis and its precious resource, the spice melange. Fitting all of that tale into movie length proved comically impossible for Jodorowsky. Lynch’s film palpably suffers from numerous cuts and recuts to the final edit, which clocks in at two hours and 17 minutes. So instead of showing not telling the story, the movie relies on a flurry of voiceover and breathy exposition. Like this:

Dune 's very language makes the movie almost impenetrable. Within the first 10 minutes, the film bombarded audiences with words like Kwisatz Haderach , landsraad, gom jabber, and sardaukar with little or no context. “Blaster,” “x-wing,” “droid,” and “force” are words for made up things but they’re words that we know. “Bene Gesserit” doesn’t have quite the same ring as “Jedi.” Reciting these words are a cast of characters thoroughly lacking in the human qualities that made even Star Wars ’ most alien beings so endearing. There’s no Han Solo here to warm up the crowd, just a collection of rigid, weird, off-putting figures speaking in hyper-dramatic, declarative tones. It’s hard to come off as less human than a beeping trash can.

After all that, it probably doesn’t sound like there’s anything worthwhile in Lynch’s film. That’s far from the truth. It’s certainly a different kind of sci fi than Star Wars , which was created to comfort and entertain. Dune wanted to challenge, and though its stumbling attempts to pontificate on religion and ecology may have been its downfall, those attempts also produced some of the film’s most resonant moments.

If the movie’s goal was to create, like the book, a world that felt utterly alien, then Lynch and his surreal style were the right choice. With its bizarre dream sequences, rife with images of unborn fetuses and shimmering energies, and unsettling scenery like the industrial hell of the Harkonnen homeworld, the film’s actually closer to Kubrick ( 2001: A Space Odyssey ) than Lucas. It seeks to put the viewer somewhere unfamiliar while hinting at a greater, hidden story.

Some scenes seem like giant WTFs: the Emperor’s meeting with the guild navigator (basically a giant mutant peanut floating in a mobile fish tank) and Paul Atreides encounter with the jom gabbar , for example. But those sequences also communicate the sense that something immense is occurring just beyond our vision. Science fiction is often about feeling just the right amount of lost.

The film’s production is masterful in itself, and it syncs with the themes of the original storyverse. Set 10,000 years in the future, everything looks appropriately streamlined. Yet plenty of baroque flourishes (the Emperor’s court in the opening scenes looks like a relic of imperial Russia) remain, as if to illustrate, as Herbert does in his novel, that even as we evolve, certain elements of our existence will remain constant. Jodorowsky’s new-age, bright and groovy acid-trip take seemed to miss this point.

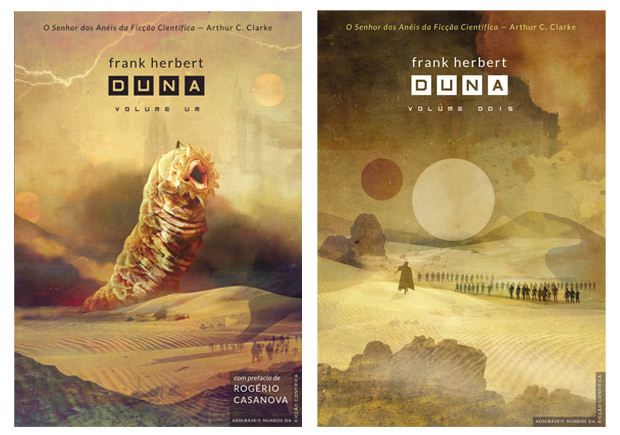

The special effects were not particularly impressive from a technical standpoint, something critics eagerly pointed out. But the miniature sets, created mostly by Emilio Ruiz del Río, achieve a staggering sense of scale. Watch the scene where the Atreides fleet departs for Arrakis. Dozens of already massive ships file into what looks like an ornate keyhole, instantly dwarfing them in the viewer’s eye and creating a sense of ponderous motion fit for a massive interstellar space craft. The novel’s iconic sandworms feel similarly gargantuan onscreen as they rumble out of the barren desert.

Before his death in 1986, Herbert said that he was largely pleased with Lynch’s film’s representation of his universe. You can understand why. While it’s hardly a cohesive experience, individual scenes are brought to life with striking power. Watching Dune today holds the same joy as flipping through an illustrated version of the novel. Considering the density and imagination of Herbert’s world, that should count as something of an achievement.